Converting Wastewater to Sustainable Aviation Fuel

Researchers at Argonne National Laboratory have developed a process that converts wastewater into biofuel components, offering a cost-competitive and sustainable alternative for SAF production

Aircraft have been fuelled by kerosene over the last century and have been emitting high volumes of Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG). Now, a new generation of sustainable aviation fuels have been developed which have the potential to halve the aviation industry’s carbon emissions by 2050. Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is a certified jet fuel ( Jet-A/A1). However, unlike traditional jet fuel that is, from fossil resources, today’s SAF is a blend of conventional fossil fuel and synthetic components that are prepared from a range of renewable “feedstock” (such as used cooking oils, fats, plant oils, municipal, agricultural and forestry waste). SAF can be blended at various levels with limits between 10 per cent and 50 per cent, depending on the feedstock and how the fuel is produced. SAF so blended with conventional Jet A can be used as drop-in fuel for the existing engine & aircraft integration.

The international aviation industry has set an aspirational goal to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, with SAF presenting the best near-term opportunity despite challenges such as high costs and limited feedstock availability

Worldwide, 12 per cent of all carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are from the transportation sector of which aviation accounts for 2-3 per cent of all CO2 emissions. ICAO’s Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) plugs the net CO2 aviation emissions at 2020 levels through 2035. The international aviation industry has set an aspirational goal to reach net zero carbon by 2050. SAF presents the best near-term opportunity to meet these goals.

SAF can be produced from a variety of non-petroleum-based renewable feedstocks like food and waste portion of municipal solid waste, woody biomass, fats/greases/oils, and other feedstocks. There are multiple technology pathways to produce these fuels which are approved by American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) and also their blending limits based on these pathways. ASTM D7566 Standard, Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuel Containing Synthesised Hydrocarbons, dictates fuel quality standards for non-petroleum-based jet fuel and outlines approved SAF-based fuels and the percent allowable in a blend with Jet A. ASTM D1655 Standard, Specification for Aviation Turbine Fuels allows co-processing of biomass feedstocks at a petroleum refinery in blends up to five per cent. Both ASTM standards are continuously updated to allow for developments in technology to produce SAF. The nine approved pathways are:

- Fischer-Tropsch (FT) Synthetic Paraffinic Kerosene (SPK): Woody biomass is converted to syngas using gasification, then a Fischer-Tropsch synthesis reaction converts the syngas to jet fuel. Feedstocks include various sources of renewable biomass, primarily woody biomass such as municipal solid waste, agricultural wastes, forest wastes, wood, and energy crops. ASTM approved this in June 2009 with a 50 per cent blend limit.

- Hydro-processed Esters and Fatty Acids: Triglyceride feedstocks such as plant oil, animal oil, yellow or brown greases, waste fat, oil, and greases are hydro-processed to break apart the long chain of fatty acids, followed by hydroisomerisation and hydrocracking. This pathway produces a drop-in fuel and was ASTM approved in July 2011 with a 50 per cent blend limit.

- Hydro-processed Fermented Sugars to Synthetic Isoparaffins: Microbial conversion of sugars to hydrocarbons. Feedstocks include cellulosic biomass feedstocks (e.g., herbaceous biomass and corn stover). Pre-treated waste fat, oil, and greases also can be eligible feedstocks. ASTM approved in June 2014 with a 10 per cent blend limit.

- FT-SPK with Aromatics: Biomass is converted to syngas, which is then converted to synthetic paraffinic kerosene and aromatics by FT synthesis. This process is similar to FT-SPK ASTM D7566 Annex A1, but with the addition of aromatic components. ASTM approved in November 2015 with a 50 per cent blend limit.

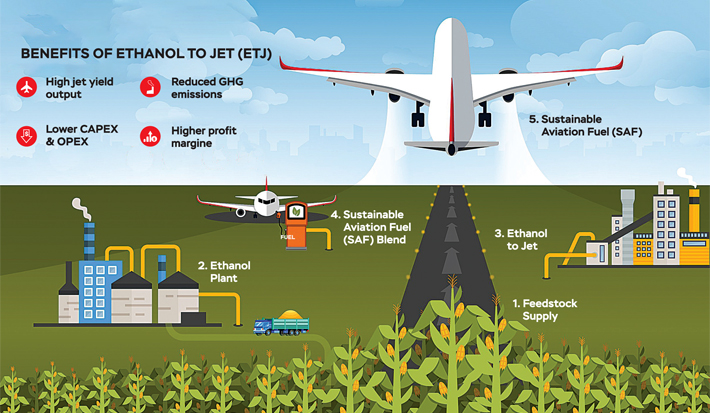

- Alcohol-to-Jet Synthetic Paraffinic Kerosene: Conversion of cellulosic or starchy alcohol (isobutanol and ethanol) into a drop-in fuel through a series of chemical reactions—dehydration, hydrogenation, oligomerisation, and hydrotreatment. The alcohols are derived from cellulosic feedstock or starchy feedstock via fermentation or gasification reactions. Ethanol and isobutanol produced from lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover) are considered favourable feedstocks, but other potential feedstocks (not yet ASTM approved) include methanol, iso-propanol, and long-chain fatty alcohols. ASTM approved in April 2016 for isobutanol and in June 2018 for ethanol with a 30 per cent blend limit.

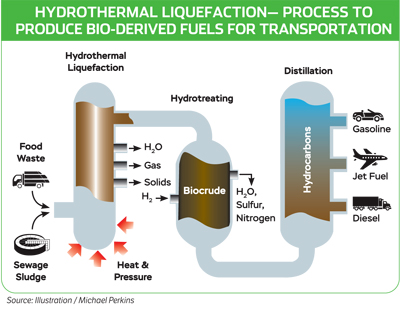

- Catalytic Hydro-thermolysis Synthesised Kerosene: (Also called hydrothermal liquefaction), clean free fatty acid oil from processing waste oils or energy oils is combined with preheated feed water and then passed to a catalytic hydrothermolysis reactor. Feedstocks for the CH-SPK process can be a variety of triglyceride-based feedstocks such as soybean oil, jatropha oil, camelina oil, carinata oil, and tung oil. ASTM approved in February 2020 with a 50 per cent blend limit.

- Hydrocarbon Hydro-processed Esters and Fatty Acids: Conversion of the triglyceride oil, derived from Botryococcus braunii, into jet fuel and other fractionations. Botryococcus braunii is a high-growth alga that produces triglyceride oil. ASTM approved in May 2020 with a 10 per cent blend limit.

- Fats, Oils and Greases (FOG) Co-Processing: ASTM approved five per cent fats, oils, and greases coprocessing with petroleum intermediates as a potential SAF pathway. Used cooking oil and waste animal fats are two other popular sources for coprocessing.

- FT Co-Processing: In association with the University of Dayton Research Institute, ASTM approved five per cent Fischer-Tropsch syncrude coprocessing with petroleum crude oil to produce SAF.

India’s first commercial passenger flight using indigenously produced SAF blend flew in May 2023, marking a milestone towards the country’s commitment to achieving netzero emissions by 2070

RECENT DEVELOPMENT OF WASTEWATER INTO SAF

Researchers at Argonne National Laboratory, USA, have developed a technology that turns wastewater from sources like breweries and dairy farms into ingredients needed to create SAF, particularly volatile fatty acids (VFAs) like butyric acid and lactic acid. This process, known as ‘methanearrested anaerobic digestion’ (MAAD), uses bacteria to break down organic matter in wastewater, converting it into these fatty acids, which can then be transformed into biofuels. The team also created an ‘in-situ product recovery process’ that utilises membrane separation technology to extract the desired organic compounds from complex wastewater mixtures. This method helps improve the yield of butyric acid, making the entire process more efficient and enabling the production of SAF at a much larger scale.

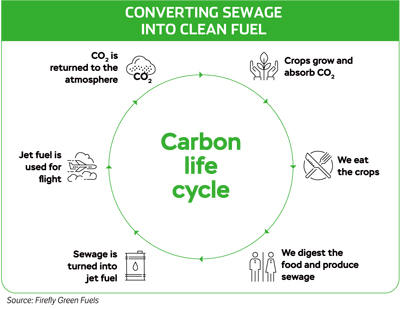

Instead of relying on conventional resources like fat, oil and grease, scientists have used carbon-rich wastewater from breweries and dairy farms as a feedstock for their innovative technology. The novel technology strips organic carbon from these high-strength waste streams that are otherwise difficult to treat economically. This unique approach creates a cleaner, more sustainable fuel alternative and also tackles the environmental problem of wastewater disposal. By converting wastewater into biofuel, the process reduces the carbon extent of traditional wastewater treatment, which contributes to harmful algal blooms and ecosystem disruption.

This path breaking technology creates a cost-competitive SAF that could reduce GHG emissions in the aviation industry by up to 70 per cent. Argonne’s life cycle and techno-economic models have been used to analyse the environmental impacts and economic viability of the SAF.

India’s abundance of ethanol feedstock and supportive policies under the Ethanol Blending Programme position the Alcohol-to-Jet pathway as the most viable option for scaling SAF production domestically

It has been indicated that scientists at Argonne National Laboratory will continue to work on improving the sustainability of their findings, and even researching other materials from feedstock that could be used with this technology. The study also expands the use of lesser-used waste materials at a time when demand for typical bio-feedstock for SAF results in a shortage. While research will continue, ultimately, scientists hope to commercialise the patent-pending process and scale the technology for widespread use. These efforts were funded by the DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office. The hope is that by funding the research efforts, scientists will meet their goal of commercialising the process and scaling it to create sufficient SAF to meet 100 per cent of the demand from the commercial sector.

HOW DOES SAF REDUCE THE AVIATION INDUSTRY’S CARBON FOOTPRINT?

Air transport represents approximately 2-3 per cent of global human-induced GHG emissions. SAF is one of the means the aviation industry is using to reduce that carbon footprint. On average, SAF can reduce CO2 emissions by 80 per cent compared to traditional jet fuel. This substantial reduction is crucial to the industry’s progress towards decarbonisation. The key to SAF’s impact lies in its life cycle. When burned, SAF still produces emissions similar to those emitted by fossil fuels. But unlike conventional jet fuels, which take fossil resources out of the ground and release previously stored carbon into the atmosphere, SAF primarily uses carbon that is part of the current carbon cycle in various feedstocks. This means that the CO2 emitted during an aircraft’s flight is re-absorbed by the biomass used in SAF production.

The SAF ecosystem is in its infancy across the globe. Limited volumes mean SAF is much more expensive than conventional jet fuel. As production expands, SAF prices will reduce, but, it still requires collaboration between governments, industry and regulators on a global scale for its large-scale infusion in the aviation fuel ecosystem. Appropriate regulatory mechanisms and innovative arrangements need to be established. Even then, there are challenges associated with the limited availability of land and biowaste. As the SAF ecosystem matures, it is expected that multiple pathways utilising the most regionally appropriate feedstocks will be established. It is clear that both biomass sources and E-Fuels will be necessary to meet the demand. (E-fuels are synthetic fuels produced through electrolysis).

DISTRIBUTION ISSUES

SAF must be blended with Jet A prior to use in an aircraft. If SAF is co-processed with conventional Jet A at an existing petroleum refinery, the fuel would flow through the supply chain in a business-as-usual model via pipeline to terminals and onwards by pipeline or truck to airports. It is expected that SAF produced at biofuels facilities would be blended with Jet A at existing fuel terminals and then delivered to airports by pipeline or truck. The fuels could also be blended at the terminal directly upstream of an airport or thousands of miles away and transported by pipeline or barge to a terminal near the airport. There would be no change to fuel operations at the airport, as airports are expected to continue to receive blended fuel in the same pipelines and trucks as they do today. While it is technically possible to blend fuels at an airport, it is not the most practical or cost-effective method due to the need for additional equipment, staff, and insurance. Due to strict fuel quality standards, it is preferable to certify SAF as ASTM D1655 upstream of an airport.

SAF IN INDIAN AVIATION

In a significant development towards decarbonising of the aviation sector, India’s first commercial passenger flight using indigenously produced SAF blend was successfully flown on May 19, 2023. Air Asia flight (I5 767) flew from Pune to Delhi fuelled by SAF blended ATF produced by Praj Industries Ltd by using indigenous feedstock, supplied by Indian Oil Corporation Ltd and used by Air Asia.

Describing the occasion as a significant milestone in the country’s efforts towards Net Zero emissions by 2070, the then Union Minister of Petroleum & Natural Gas and Housing & Urban Affairs, Hardeep Singh Puri had said, “This would be the First domestic commercial passenger flight with SAF blending up to one per cent as demonstration mode”. “By 2025, if we target to blend one per cent SAF blending in Jet fuel, India would require around 14 crore litres of SAF/annum. More ambitiously, if we target for five per cent SAF blend, India required around 70 crore litres of SAF/annum”. With a focussed vision of Atmanirbhar Bharat, the Petroleum Minister said, “Production of SAF using sugarcane molasses as indigenous feedstock and technology in India is a major step towards self-reliance and de-carbonisation of the aviation sector in line with our commitment for achieving Net Zero by 2070.”

Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) has the potential to halve the aviation industry’s carbon emissions by 2050, with lifecycle emissions reductions of up to 80 per cent compared to traditional jet fuel

India is blessed with a variety of feedstocks (both sugar, starch, and lignocellulosic) in abundance. These feedstocks are the basic ingredients for SAF production via the Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) pathway. There are nine pathways already approved and certified by ASTM globally. Sachin Raole, the CFO, Praj Industries, has indicated that, “For India, the ATJ is the preferred pathway because of the substantial availability of ethanol with supportive policies and an ecosystem well established with the Ethanol Blending Program in action. Under the ATJ pathway, multiple alcohol like ethanol, isobutanol, etc, can be converted into SAF.”

Globally the SAF cost is about 2-3 times that of ATF which is largely due to the high prices of the feedstock i.e., low CI ethanol, which is the main contributor to the cost of SAF production via the ATJ pathway. Raole has detailed that, “A clear and firm long-term policy is necessary for the SAF growth in India. The expectation from the government would be to come up with a definite pricing framework. For some early projects, special pricing, or viability gap funding (VGF) is required. Similarly, clarity on offtake agreements, take or pay agreements, would help participating stakeholders make concrete investments and decisions in the SAF sector”.

Although India has embarked on the path for the use of SAF blend in ATF, the commercial viability of SAF production poses a significant challenge to the successful commercialisation of SAF in India. India is still taking baby steps, but if the oil companies, feedstock producers and aviation industry put their heads together they can work out a reasonable way of promoting SAF, considering the domestic market’s price sensitivity. The government of India is likely to come up with mandates for blending of SAF with aviation ATF for domestic flights only after the global mandates for international flights kick in from 2027.