Is Aviation Net Zero 2050 Feasible?

Achieving net zero by 2050 requires immediate, collaborative, and transformative action from governments, airlines, manufacturers, and other stakeholders to invest in SAF, cutting-edge technologies, and innovative operational efficiencies

The news about global warming leading to climate change gets worse by the day. In October 2024, a new UN report warned that without determined action to decarbonise the economy the world could warm by a huge 3.1C this century, leading to dramatic increases in extreme weather events, including heatwaves and floods. It says that the goals of the Paris Agreement to keep global warming under 2C while making efforts to stay below 1.5C are now in very serious danger. The landmark Paris Agreement of 2015, that sought to address climate change and its negative impacts, was adopted by nearly every nation of the world. Pledges galore followed. Indeed, if every country simply puts their stated plans into action and honours their own net zero pledges, the global temperature rise could still be contained to 1.9C. Yet action on the ground has been unimpressive, to say the least.

Currently, only about 10 per cent of the global population flies and aviation accounts for just 2.5 per cent of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. But when non-CO2 effects are included, aviation’s contribution to global warming increases to approximately 4 per cent. This figure could triple by 2050, as rising incomes encourage more people to travel by air. The International Air Transport Association (IATA), at its Annual General Meeting in October 2021, pledged to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Adding weight to this decision, in October 2022, member states of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) also agreed to a long-term aspirational goal (LTAG) of net zero emissions from aviation by 2050. Net zero means the amount of GHG removed from the atmosphere is equal to that emitted by the specific human activity, in this case aviation.

Is aviation net zero by 2050 an achievable goal? Some analysts declare that it is unlikely, perhaps even impossible. However, while recognising that aviation is one of the most stubbornly difficult industries to decarbonise, IATA asserts that net zero by 2050 is definitely practicable. To bolster its claims it has released five net-zero roadmaps. Researchers at the University of Cambridge broadly agree. They have released their own blueprint which says the sector could reach net zero by 2050 if urgent action is taken in the next five years.

IATA’S NET ZERO ROADMAPS

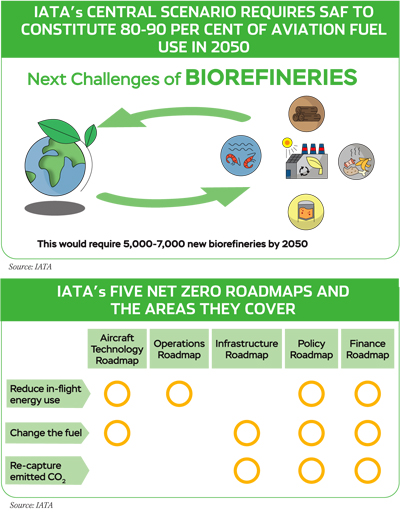

IATA’s five roadmaps are a step-by-step listing of the main actions required to be taken not just by the aviation industry, but also by governments, suppliers, and financiers, to accelerate the transition to net zero by 2050. They were formulated by comparing 14 leading aviation net zero transition roadmaps. According to Willie Walsh, IATA’s Director General, “The roadmaps are a call to action for all aviation’s stakeholders to deliver the tools needed to make this fundamental transformation of aviation a success with policies and products fit for a net-zero world.” IATA says that success will depend mainly on early policy support and the pace at which solutions are implemented.

- Aircraft Technology Roadmap: Around 15-20 per cent improvement in jet aircraft efficiency, compared to the best technology today, is still achievable. In addition, all next-generation aircraft must be capable of operating on 100 per cent Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF). Key milestones for conventional aircraft are already backed by investment and demonstrator programmes, including new engines, aerodynamics, aircraft structures and flight systems. However, what is urgent and essential, is the development of revolutionary aircraft that will be operated with hydrogen or batteries, fully eliminating carbon emissions from their operations.

- Energy and New Fuels Infrastructure Roadmap: In IATA’s thinking the widespread transition to SAF is the single most important factor on the road to net zero. The airline industry will require assured SAF infrastructure upstream from the airport ( for feedstock collection, refining, and blending). IATA’s central scenario requires SAF to constitute 80-90 per cent of aviation fuel use in 2050, which would reduce emissions by 62 per cent. To achieve this massive transition, IATA estimates that 5,000-7,000 biorefineries will be required for aviation alone by 2050. That’s not all. To produce such vast amounts of SAF, the aviation sector could require close to 100 Mt of hydrogen by 2050, an amount comparable to all hydrogen production worldwide in 2023.

- Operations Roadmap: According to IATA, air traffic management should be treated as a key part of national infrastructure and prioritised in the overall strategy for sustainable aviation.

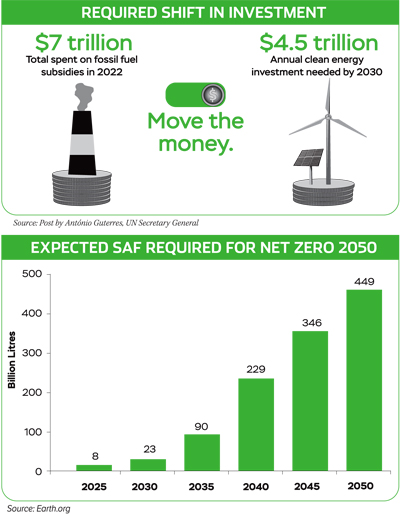

- Finance Roadmap (September 2024 update): According to this Roadmap, to reach net zero by 2050, the annual average capex needed to build new facilities over the 30-year period is about USD128 billion per year. Success would be easier if governments redirected subsidies away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy production. The most important determinant of how many new facilities need to be built is probably the proportion of SAF production in refineries’ total output. This is because SAF is often competing with other refinery products like biodiesel. Hence a major reduction can be achieved in the number of new plants, and the corresponding investment, by maximising SAF co-processing at existing refineries. Co-processing involves inserting a bio-based intermediate into existing petroleum refineries for simultaneous processing with petroleum feeds. This will increase SAF volumes immediately as it requires neither lead time nor additional investments.

- Policy Roadmap (September 2024 update): This emphasises the critical importance of strategic policy sequencing and the need for global collaboration, including beyond the aviation sector.

IATA lists four key conclusions of the five roadmaps:

- The air transport industry’s energy transition is feasible on the 2050 horizon.

- The amounts of investments needed to make that possible are comparable to those engaged in previous creations of new renewable energy markets.

- Success in the transition depends critically upon policymakers’ unity of purpose.

- The time left for joining forces in air transportation’s energy transition is shrinking by the minute. Every action delayed is an opportunity missed.

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE REPORT

A report entitled “Five Years to Chart a New Future for Aviation”, published in September 2024 by the University of Cambridge’s Aviation Impact Accelerator (AIA) global initiative, outlines an ambitious five-year plan to shift the aviation sector onto a sustainable path. It establishes four pivotal 2030 Sustainable Aviation Goals, each targeting key leverage points within the sector. If initiated in 2025 and implemented within the next five years, these could help set the sector firmly on the road to net zero 2050.

- Goal 1: Operation Blue Skies: Governments and industry need to create several ‘Airspace-Scale Living Labs’ to enable a global contrail avoidance system to start to be deployed by 2030. Contrail avoidance can potentially deliver quick environmental gains for the industry, giving it more time to switch to SAF.

- Goal 2: Systems Efficiency: Governments should signal a clear commitment to the market about their intention to drive system-wide efficiency improvements. In tandem, efficiency strategies need to be developed so that, by 2030, a new wave of policies can be implemented to unlock these systemic efficiency gains.

- Goal 3: Truly Sustainable and Scalable Fuel: Governments should reform SAF policy development to adopt a cross-sector approach, enabling rapid scalability within global biomass limitations. This would help SAF production to move beyond purely biomass-based methods, incorporating more carbonefficient synthetic production techniques.

- Goal 4: ‘Moonshots’: Several high-reward experimental demonstration programmes need to be launched to enable the focus on, and scale-up of, the most viable transformative technologies by 2030.

Echoing an IATA conclusion, the authors of the AIA stress that time is of the essence for these four interventions to have the desired impact.

SAF REIGNS SUPREME

A common feature of every roadmap to aviation net zero is SAF. SAFs are synthetic alternatives to fossil fuels, made from renewables like waste cooking oils, vegetable fats and agricultural waste, which are rather limited. An alternative and practically unlimited production method is called ‘power to liquid’ (PtL), in which water and CO2 are broken down, with the resulting carbon and hydrogen combined to create liquid fuel. In order to be truly sustainable, PtL would require large quantities of renewable electricity, as well as a substantial increase in carbon capture and storage. However, although SAF production is expected to triple to 1.875 billion litres in 2024, this amounts to just 0.53 per cent of aviation’s fuel needs and 6 per cent of total renewable fuel capacity. According to IATA, as much as 449 billion litres of SAF will be required by 2050.

New technologies to power aircraft, such as hydrogen power and electrification, are likely to play a role, at least on shorter routes, by the early 2040s. But hydrogen is bulky and difficult to store in the huge quantities necessary to power aviation on a large scale. To be sustainable, it has to be made from renewable sources of which supplies are limited. Batteries are very heavy in relation to the energy they contain. Neither can they power large planes, nor last over long distances. In contrast, SAF is a ‘drop-in’ fuel – ready to be used in today’s aircraft.

IATA says that success of net zero 2050 will depend mainly on early policy support and the pace at which solutions are implemented

However, at present SAF is so much more expensive than normal fuel, and its supply is so limited, that it may take decades to attain financial viability. Besides, the vast and hurried expansion of production required to feed the growing thirst of the airline industry comes with environmental and societal risks. Prime among these is the already rampant diversion of forested areas and fertile land for food crops – to crops for SAF production.

Overdependence on SAF as a solution also discourages other more lasting options to curb carbon output, like designing and developing true zero-emission aircraft. In July 2024, Airbus projected that the global fleet of commercial passenger and freighter aircraft will roughly double during the next 20 years, from 24,260 today to 48,230 in 2043. Boeing predicts a similar trend. A July 2024 report from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) warned that the aviation industry will miss its netzero goal unless all new aircraft delivered after 2035 are net zero over their entire operational lifetimes. Unfortunately, all indications are that Airbus and Boeing’s next-generation jets will be of relatively conventional design, with fuel-burning engines, and only incrementally more efficient than current airliners.

TIME IS OF THE ESSENCE

Planet Earth is sitting on a ticking time bomb. Climate change poses an existential threat to humanity, with global warming intensifying natural disasters, and devastating impacts on ecosystems and biodiversity. This underscores the need for urgent collective action to reduce GHG emissions and transition to a more sustainable future. Therefore, the aviation industry’s growing awareness of its need to achieve environmental sustainability is encouraging. However, its eloquently articulated intentions need to be backed with decisive interventions over the next five years to create a feasible path to net-zero aviation by 2050.

The road ahead is subject to numerous uncertain factors involving technology, regulations, government policies, and geopolitics. At present many of these are dangerously off track. For instance, all indications are that the new Trump administration in the US may not be particularly environmentally friendly. And in a telling sign of how fragile even ‘firm’ commitments are, Air New Zealand – a company previously heralded as one of the most sustainabilityfocused airlines – has abandoned its 2030 carbon intensity reduction targets. It blamed lack of political support, limited aircraft technologies, and a shortage of SAF. Thankfully, it has retained its commitment to reach net-zero emissions by 2050. Other carriers may be forced to follow suit. Indeed, IATA laments that it is impossible today for many airlines to meet the obligations that are being imposed on them, without necessary supportive action.

Yet, it would be wrong to succumb to despair. According to Willie Walsh, IATA’s director general, “The updated IATA Policy and Finance Net Zero Roadmaps make it clear that decarbonisation by 2050 is possible. They also sound a warning bell that, to achieve this, all stakeholders, particularly policymakers, must collaborate more broadly and act with greater urgency.”

Achieving net zero by 2050 requires immediate, collaborative, and transformative action from governments, airlines, manufacturers, and other stakeholders to invest in SAF, cutting-edge technologies, and innovative operational efficiencies. In a nutshell, what is needed is less talk and more action.