Wanted: Action on SAF!

With SAF being constantly pushed as a panacea, a reality check is essential. The journey to achieve net zero by 2050 will in truth be long, arduous and terribly expensive. Success is by no means assured without urgent measures.

Airline strategy is now increasingly influenced by environmental sustainability. Both the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Air Transport Association (IATA) have set impressive climate goals. In October 2022, ICAO member states agreed to a long-term aspirational goal (LTAG) of net zero emissions from aviation by 2050. This followed the aviation industry’s commitment to the same net zero objective, adopted by IATA in 2021. Net zero means the amount of greenhouse gases (GHG) removed from the atmosphere is equal to that emitted by that activity.

The quest for sustainability is driven by growing fears of irreversible climate change. In February 2024, for the first time, global warming exceeded 1.5 degrees C through a full year. “Why lose sleep over this?” climate sceptics demand, adding that ups and downs in the global temperature trend have been recorded throughout history. But an overwhelming majority of scientists believe that 1.5 degrees is a climate change “red line” and overshooting it even for a few years may trigger tipping points that cannot be uncrossed – such as the melting of permafrost that would, in turn, release huge amounts of trapped CO2 and intensify global warming. If proof were needed, the planet experienced record floods, droughts, heatwaves and wildfires in 2024. Another half degree temperature rise could greatly intensify these effects.

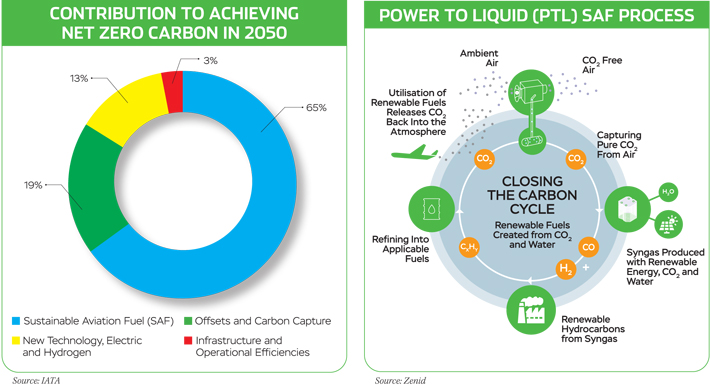

Where does aviation stand? Although flying is very carbon intensive it contributes just 2.5 per cent of global emissions. But thanks to non-CO2 emissions, soot and contrails, aviation’s total contribution to global warming is more than twice that figure. While engine manufacturers constantly strive to increase fuel efficiency, the gains are dwarfed by soaring demand for aviation services. Convinced of the need to act, the aviation industry has adopted a multi-pronged approach that banks mainly on sustainable aviation fuel (SAF). In fact, in IATA’s thinking, as much as 65 per cent of carbon mitigation required to achieve net zero by 2050 will come from SAF.

Yet, many major questions remain unanswered. Is the aviation industry’s commitment to sustainability strong and lasting? Can it afford the cost? Will it bear the pain? Even with the best of intentions, can SAF production be steeply ramped up in time to attain the 2050 net zero goal? Unfortunately, action so far – as opposed to mere aspiration – does not offer much hope. So what needs to be done?

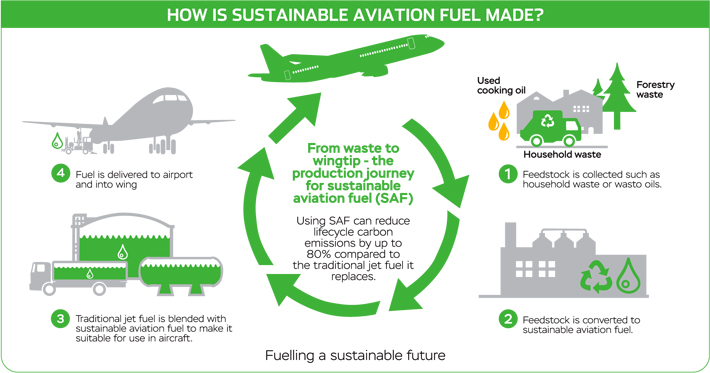

SAF is a synthetic replacement for regular jet fuel, made from renewable sources like waste cooking oils, vegetable fats and agricultural waste, as well as captured CO2. While fossil fuel releases carbon that has been stored in the earth for millions of years, the carbon generated by SAF has only recently been removed, either by plants or by chemical processes. Therefore, SAF does not add to the overall amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Apart from this direct CO2 benefit, SAF reduces the particulates and smoke that emerge from the engine and enhance contrails. Contrails are increasingly seen as deadly by climate scientists.

SAF is a “drop-in” fuel meaning that since its chemical composition is very similar to normal fossil fuel the two can be used interchangeably. Although current regulations only permit up to 50 per cent of SAF in jet fuel blends, efforts are on to clear even 100 per cent SAF. However, the process is slow. Both Airbus and Boeing have pledged to make their aircraft fully compatible with 100 per cent SAF by 2030.

Advocates of SAF claim that it can reduce emissions by up to 80 per cent across the lifecycle of the fuel, with a 100 per cent reduction possible in future. However, some recent studies have concluded that the emissions created in flight are considerable and that the benefits of SAF may be rather less than estimated. There are also concerns about secondary environmental impacts, including SAF feedstocks being grown as cash crops and usurping land used for food production. A 2023 report by the UK-based Royal Society said biofuels do reduce emissions, but that many estimates do not account for “land use changes”. Accounting for those changes “significantly” impacts estimated carbon output, and “few hit the renewable energy directive target”.

HOW IS SAF PRODUCED?

SAFs can be produced from a variety of feedstocks and through several different technologies. As of July 2023, 11 conversion processes for SAF production had been approved and seven other processes were under evaluation.

- First Generation SAFs: These are the cheapest, simplest to produce and hence most commonly available types. They come mainly from fats, oils and greases (FOGs). However, limited availability of feedstocks prevents significant scaling up of production.

- Second Generation SAFs: These are obtained from abundant biomass sources like algae, crop residues, animal waste, forestry residues and sludge as well as from municipal solid waste. But production requires advanced technologies and complex processes that are expensive and energy-intensive.

- E-Fuels: Also known as electrofuels, these are prepared from renewable energy and captured CO2. They are made using a “power to liquid” (PtL) process that produces liquid hydrocarbons synthetically. Although very expensive, they could potentially produce unlimited supplies of SAF. To be truly sustainable they need large quantities of renewable electricity, as well as a substantial increase in carbon capture and storage capacity.

CHIEF CHALLENGES

According to the Geneva-based Air Transport Action Group (ATAG) over 7,75,000 commercial flights have been operated using SAF since 2011. Worldwide, 69 airports are currently regularly supplied with SAF. And 50 airlines have committed to 2030 SAF goals ranging from 5-30 per cent of their total fuel usage, with most committing to 10 per cent. It all looks rosy. However, formidable challenges lie ahead.

- Price: The main issue is producing SAF at scale, across the globe, at an affordable price. This seems a distant dream because SAF currently costs between three and five times as much as regular jet fuel.

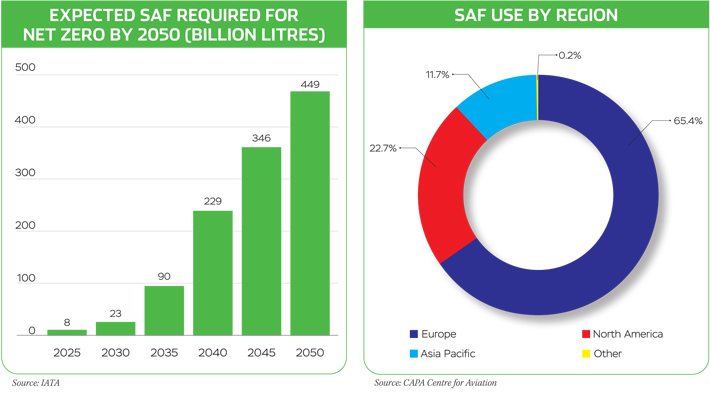

- Production: According to IATA, around 600 million litres of SAF were produced in 2023. Production is expected to more than triple in 2024, to around 1.9 billion litres. Even this will constitute just 0.53 per cent of the total jet fuel consumed during the year. An ICAO sponsored goal of five per cent CO2 emissions reduction by 2030 would need around 27 per cent of global renewable fuel production capacity to be devoted to SAF. However, SAF currently accounts for just three per cent of such production. Another daunting figure – in order to reach the 449 billion litres annual SAF production capacity that the 2050 net zero goal is overwhelmingly dependent on, the CAGR needs to be 23.39 per cent.

- Patchy Usage: Every drop of SAF is purchased but the users are mostly full-service and network airlines. According to the CAPA - Centre for Aviation, the ubiquitous LCCs are less likely to adopt SAF enthusiastically since fuel typically accounts for a large proportion of their operating costs. Due to limited renewable fuel availability, airlines will also need to purchase much more expensive types like e-fuels. European airlines are mainly driving SAF adoption, accounting for around two thirds of globally reported SAF use. North America, although the world’s largest aviation market, is way behind. More worryingly, SAF usage is still low in the fast-growing Asia Pacific region and practically non-existent in the rest of the world.

- Political Pressures: A second Donald Trump presidency would quite likely be a nightmare for Earth’s climate. It may be recalled that in his first term, Trump pulled the US out of the 2015 Paris climate agreement, rolled back environmental regulations, unleashed large-scale oil and gas drilling and much more. Recent reports quote his advisors as believing he did not go far enough. They are openly planning an “all-out war on climate science and policies”. Where would that leave the Biden administration’s “SAF Grand Challenge” goal of producing sufficient SAF to meet 100 per cent of US demand by 2050? In July 2024, even the European Commission, otherwise a staunch proponent of strong action to mitigate global warming, succumbed to pressure from legacy airlines and excluded long-haul flights from the scope of its non-CO2 aviation emissions monitoring scheme that commences in January 2025. This means that 67 per cent of European aviation’s contrail climate impact will be ignored for at least another two years.

SEEKING SOLUTIONS

Accelerating production and reducing the cost of SAF is imperative and will best be achieved by a combination of urgent measures. Some of these are:

- Diversifying Feedstocks: The global supply of hydrogenated fatty acids (HEFA) like used cooking oils and animal fats could soon run out. Focussing on other certified pathways and feedstocks will “greatly expand the potential for SAF production,” according to IATA.

- Exploiting Existing Refineries: Crude oil refineries should be mandated to co-process a small but increasing percentage of approved renewable feedstocks too. This could quickly scale up SAF production.

- Increasing Aviation’s Share: As mentioned earlier, SAF constitutes just three per cent of renewable fuel. Other sectors that grab the lion’s share – like transportation – should be incentivised to go electric, leaving more of the pie for aviation. The switch from diesel to SAF requires only minimal modification of existing renewable fuel facilities.

- Boosting Investment: An investment of over $1 trillion may be required to create enough SAF production capacity for 2050. Government support is crucial. The big energy companies should also be compelled to invest some of their huge profits in SAF.

- SAF Mandates and Subsidies: The long-term trend is expected to be a reduction in SAF production costs enabled by economies of scale and technological advancements, provided demand is assured. Governments can help with strict mandates and generous incentives to use SAF. The EU, for instance, has introduced regulations that include mandates to use SAF starting at two per cent from 2025 and increasing to six per cent by 2030. The US offers subsidies to bring down the price of sustainable fuels. India has set a target to blend one per cent SAF with jet fuel in 2027 and two per cent in 2028. However, these will apply only to international flights initially.

- Pursuing Contrail Mitigation: Recent research suggests that contrails could have a greater climate impact than CO2 emissions and that reducing the amount of soot emitted can reduce contrail persistence. Contrail management therefore could potentially deliver quick environmental gains for the industry, giving it more time to switch to SAF. The most heartening finding is that SAF results in less persistent contrails.

ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS!

Matt Finch, UK head of campaign group Transport & Environment says, “There are good SAFs, and there are bad SAFs, but the brutal truth is that right now there is not much of either. Conversely, right now there are thousands of new planes on order from airlines, and all of them will burn fossil fuels for at least 20 years. Actions speak louder than words, and it’s clear that the aviation sector has no plans to wean itself off its addiction to pollution.”

Finch’s opinion may seem unduly harsh since the aviation industry is indeed sincere in its desire to attain environmental sustainability. Yet, it is undeniable that traffic growth will far outstrip efficiency improvements for the foreseeable future, thus increasing carbon emissions. IATA’s strategy therefore rests heavily on SAF. Too heavily perhaps? Just a couple of high-profile accidents even partly attributable to the use of SAF could prove a severe setback.

The cost of SAF will surely fall with higher production levels and economies of scale. However, it is unlikely that it can ever match regular fuel costs. But if not SAF, what? In the near term, there is a woeful lack of alternatives. Battery-powered planes are suitable only for short flights of small aircraft. Hydrogen will probably take decades to overcome technological and infrastructural barriers, problems of scalability, and even environmental concerns.

Yet, with SAF being constantly pushed as a panacea, a reality check is essential. The journey to achieve net zero by 2050 will in truth be long, arduous and terribly expensive. Success is by no means assured without urgent measures. Will the aviation industry shoulder its responsibility to curb emissions, no matter what the cost, even reducing flying if necessary? If not, will planet Earth ever forgive us?