Next Generation Airliners

Next-generation airliners will feature innovative airframe designs, utilising lighter and stronger composite materials and advanced aerodynamic shapes with alternative propulsion systems to enhance fuel efficiency and reduce carbon emissions.

The aviation industry has made a commitment to achieving “net-zero” carbon emissions by 2050. But this ambitious target cannot be achieved using existing aircraft technologies. New airframe designs, alternative propulsion systems and low-carbon energy sources, as well as innovative solutions to existing challenges, will help significantly reduce CO2 emissions in future aircraft.

Human beings continue to emulate the birds to make civil aviation more efficient, eco-friendly, sustainable, with longer range, smoother ride, and greater passenger comfort. This is aimed to be achieved through better aerodynamic design, lighter but stronger composite materials, and more efficient and eco-friendly fuel burning engines with lower carbon emissions.

NASA and MIT in the US have come up with a radical new aeroplane wing design that is not only much lighter than conventional wings, but also has the potential to automatically reconfigure itself to meet the flight conditions of the moment – just like birds do when they’re in mid-flight. Built out of tiny, identical polymer tiles they promise faster, cheaper aircraft production and maintenance.

More options such as supersonic bi-directional flying-wing that will allow lower speed take-off, yet, go supersonic in flight. For subsonic mode, the airplane will be rotated 90° so that the side of the airplane during supersonic flight becomes the front of the airplane. This ‘airliner of the future’ has a radical new wing design. Many more projects are evolving. Each has its advantages and challenges.

Blended flying-wing design is generally evolving as the concept has got well researched with years of military plane operations.

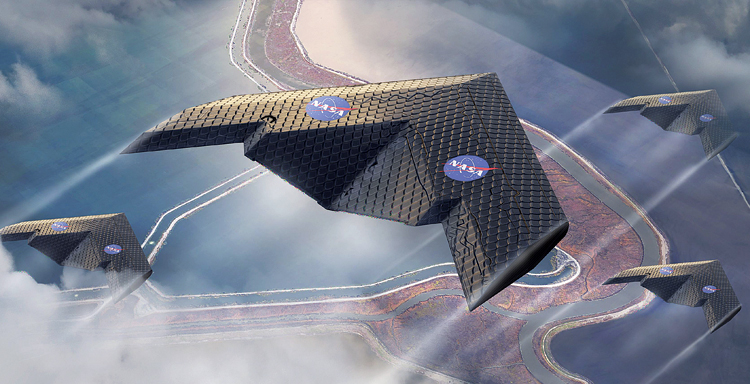

BLENDED WING BODY (BWB) CONCEPT

The blended wing body (BWB) concept offers advantages in structural, aerodynamic and operating efficiencies over today’s more conventional fuselage-and-wing designs. These features translate into greater range, fuel economy, reliability and life cycle savings, as well as lower manufacturing costs. They also allow for a wide variety of potential military and commercial applications. The first scaled model of KLM Royal Dutch Airlines’ futuristic Flying-V aircraft designed by Delft University of Technology flew in 2020.

Airbus ZEROe blended wing concept was unveiled in 2020. ZEROe programme will have three hydrogen-powered, zeroemission aircraft, which can carry 100 to 200 passengers. Airbus’ ambition is to bring to market the world’s first hydrogen-powered commercial aircraft by 2035. To get there, the ZEROe project is exploring a variety of configurations and technologies, as well as preparing the ecosystem that will produce and supply the hydrogen. In the case of hydrogen combustion, gas turbines with modified fuel injectors and fuel systems are powered with hydrogen in a similar manner to how aircraft are powered today. A second method, hydrogen fuel cells, creates electrical energy which in turn powers electric motors that turn a propeller or fan. This is a fully electric propulsion system, quite different to the propulsion system on aircraft currently in service. The race for hydrogen-powered commercial aviation has started on the ground. Hydrogen has to be produced, transported and stored in the right quantity, at the right time, place and cost. Its production and use must be regulated and certified. Airbus and ZeroAvia have signed to study the feasibility of hydrogen infrastructure at airports, initially in Canada.

(Right) CRANE X-Plane configuration in development for flight testing Active Flow Control (AFC) technologies.

In addition to Boeing and Airbus, California-based JetZero, has set an ambitious goal of putting into service a blended wing aircraft. JetZero wants to simultaneously develop three variants: a passenger plane, a cargo plane and a fuel tanker. The US Air Force has just awarded JetZero $235 million to develop a full-scale demonstrator and validate the performance of the blended wing concept. First flight is expected by 2027, which means the military version of the plane is scheduled to lead the way and perhaps support the development of the commercial models. The plane will initially borrow engines from today’s narrow-body aircraft, like the Boeing 737. Eventually the plan is to move to completely emission-free propulsion powered by hydrogen, which would require new engines that haven’t yet been developed.

COMPLEXITIES OF BWB AIRLINER

A wing that is made deep enough to contain the pilot, troops/passengers, engines, fuel, undercarriage, and other necessary equipment will have an increased frontal area when compared with a conventional wing and long-thin fuselage. Boeing has been studying possible applications for civilian and military transports. Boeing and NASA have been developing a flying-wing passenger airplane that can carry 800 passengers per flight (160 more than a 747). The current airliners fly around 950 kmph. Achieving the same in a much thicker flying wing would mean higher drag, higher engine power, and, consequentially, higher fuel consumption.

The radically new BWB airliner shape would make the planes interiors wildly different to even today’s wide-body aircraft. It’s much, much wider fuselage could have 15 or 20 rows across the cabin, depending upon how each particular airline will configure it. Passengers not having windows, would require giving artificial screens to project external view. Entry and Exit doors for boarding would require reconfiguring. So will be emergency exit doors. The much larger cabin would require a freshly designed pressurisation system. The airport infrastructure, including parking areas and aero-bridges would have to be redesigned.

The target of operationalisation by 2030 seems ambitious. Building an entirely new airplane from scratch is an enormous task, given that the full process of certification for even a variant of an existing aircraft can take years.

SUSTAINABLE FLIGHT DEMONSTRATOR

NASA and Boeing are collaborating to create the X-66A aircraft ‘Sustainable Flight Demonstrator’, which will feature long wings supported by trusses. It could first fly in 2028. Imagine a typical Boeing 737 airliner fuselage, having a high wing and another wing protruding out from the lower part of the plane’s body, effectively creating another large lifting surface. The long skinny wings are more slender and lengthier than typical wings on commercial aircraft and require a connecting brace. The brace also stabilises the wing from possible flutter that may naturally happen in a long thin wing. These will be 30 per cent more efficient and reduce carbon emissions to meet the industry’s demands to decarbonise.

(Right) Embraer ENERGIA H2 uses dual-fuel that enables it to power a gas turbine with two different fuel sources (SAF or Hydrogen).

The two-engine aircraft could have a single or two aisles. Even the connecting trusses, or braces generate lift like the old biplanes. The wings also produce less drag because they can reduce vortices at the wing tips. Some are calling it the Transonic Truss-Braced Wing (TTBW). The long wings and trusses would create the challenge of fitting into the parking gates at the airport. NASA plans to get this futuristic bird flying by 2028, and could be in service in the 2030s.

AIRBUS UPNEXT PROGRAMME

Airbus and Boeing are trying out new wing configurations for sustainability, and more. Planes with flapping wings may sound more like fiction, but could shape the next generation of business and commercial jets. Some radical wing configurations that change form to counter turbulence, while increasing efficiency. The eXtra Performance Wing that Airbus is developing part of its UpNext programme, “mimics a bird’s feathers and adjusts automatically to maximise aerodynamic flow.” Flight tests for the 165-footlong shape-shifting wing will soon year on a Cessna Citation VII jet. Like a bird, it dynamically adapts to conditions, using active control technologies. And its folding wingtips, an ancillary design, will allow for increased performance while fitting into the constraints of the airport gates.

EMBRAER’S ENERGIA PROGRAMME

Embraer is designing the future of aviation to have a lower impact. It means lower emissions, lower noise levels and lower fuel consumption. To achieve our goals, we’re exploring a wide range of bold but viable aircraft designs in our Energia concepts– reimagining and conceptualising everything from the aircraft’s power source to the shape of the airframe – all to achieve the industry-wide goal of net carbon zero by 2050. Their Energia project is exploring a range of sustainable concepts to carry up to 50 passengers. This project is considering a number of energy sources, propulsion architectures and airframe layouts to reduce carbon emissions by 50 per cent starting from 2030.

Combining a mix of technologies, hybrid-electric propulsion harvests the benefits from maximising thermal and electric engines synergies. By developing higher capacity and longer-lasting batteries, a full-electric aircraft, designed for short-range missions, could reduce the aircraft CO2 emissions to zero. Hydrogen is a highly promising area as Hydrogen fuel cells have the potential to either run as a single power source or as a hybrid with gas turbines or batteries. Dual-fuel powers a gas turbine with two different fuel sources (SAF or Hydrogen), to maximise operational flexibility and reduce aircraft weight. Using a modified gas turbine, adapted to these new fuel sources, we can increase range and passenger capacity.

CITYAIRBUS NEXTGEN

CityAirbus NextGen is an all-electric, four-seat vertical take-off and landing (eVTOL) multicopter prototype featuring a fixed wing and V-shaped tail. This helicopter demonstrator has the potential to reach speeds of 400 km/h, which is significantly faster than standard helicopters. The advanced design also means it will be 10-15 per cent more efficient than standard helicopters. It will serve for safe and reliable passenger transport, medical services or ecotourism missions, and advance urban air mobility services in countries around the world.

OTHER MEANS OF POWERING

There are other ways of trying to make aircraft greener, including running smaller planes on purely electric power to using sustainable aviation fuel. On September 24, 2020, ZeroAvia flew the world’s largest hydrogen-powered aircraft at Cranfield Airport in England, showing the possibilities of hydrogen fuel for aviation. While some are exploring hydrogen power, others are testing electric planes. Washington State-based Eviation Aircraft is behind the nine-passenger all-electric Alice aircraft, which produces no carbon emissions. In April 2024, Skydweller Aero has conducted the first autonomous flight of its solar-powered, heavypayload, long-endurance uncrewed aircraft, a modification of the Solar Impulse 2 aircraft that flew around the world on solar power in 2015-16. On March 25, 2022, an Airbus A380, the world’s largest commercial passenger airliner, completed a test flight powered entirely by SAF — sustainable aviation fuel — composed mainly of cooking oil.

BI-DIRECTIONAL FLYING WING

NASA is evolving the revolutionary supersonic bi-directional flying wing that has the potential to revolutionise supersonic flight with virtually zero sonic boom and ultra-high aerodynamic efficiency. The plan form will be symmetric about both the longitudinal and span axes. For supersonic flight, the plan form can have as low aspect ratio and as high sweep angle as desired to minimise wave drag and sonic boom. For subsonic mode, the airplane will rotate 90 degree in flight to achieve superior stable aerodynamic performance.

AIR JET FLIGHT CONTROLS

Recently, the US agency DARPA okayed construction of X-65 plane with air jet flight controls, a new technology that replaces moving control surfaces with Active Flow Control (AFC) actuators that use jets of air for control. The X-65 is an experimental jet being developed by the Control of Revolutionary Aircraft with Novel Effectors (CRANE) programme. Since the first aircraft were invented, they have been controlled by moving surfaces such as rudders, flaps, elevators and ailerons. The CRANE programme aims to do away with these entirely and develop an aircraft controlled fully by jets of pressurised air that alter how the surrounding air flows over the aircraft while in flight. If successful, it could be a gamechanging leap for all types of aircraft.

OTHER ADVANCED TECHNOLOGIES

Use of 100 per cent sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) will soon be possible. Electric propulsion for urban air mobility, such as the self-flying, battery-electric aircraft will happen soon. Solar power is seeing advances. And then there’s hydrogen, which has great potential as long as it can be produced from low-carbon sources rather than fossil fuels. Hybrid power will be the way to go. Aluminium alloys are ideal for hydrogen storage, as witnessed by their use in the tanks of space vehicles.

(Right) eXtra Performance Wing project aims to improve flight performance by completely rethinking aircraft wings.

Advances in materials technology and computing will open the door to radical, futurist new designs for a more eco-efficient plane. Morphing, the change of aircraft geometry that allows change in shape of the aircraft in nearly real time, making it more manoeuvrable, more fuel efficient will soon be an achievable objective.

Full advantage of 3D printing technologies and design bionic structures that are strong and light is happening. It will be possible to experiment with more complex shapes like birds, butterflies, fish, using biomimicry. Airbus’ “Maveric” is a blended wing body passenger plane resembling a stingray without a tail.

CONCLUSION

For long the commercial aviation prioritised safety, favouring tried-and-tested traditional ‘tube and wing’ design, and made only small innovations in airframe design and concentrated more on efficiency of engines. The blended wing body is meant to change that. It will increase payload and efficiency.

It remains to be seen whether a 50 per cent reduction in fuel use is actually possible as both NASA and Airbus quoted a more modest 20 per cent for their designs. Extensive aerodynamic testing and optimisation are essential to fully realise the drag reduction potential of this innovative aircraft design. 2030 entry is unrealistically ambitious.

Civil aviation will continue to grow exponentially. Despite growing numbers many airlines are struggling to make profits. In a very competitive world, efficient flight will be at premium. Technology will continue to step in. Great funding is required for Research and development. India must start working towards own airliners and aero-engines if it has to sit on the global high table.