Beyond Borders, Between Boundaries

International aviation is regulated by a complex web of over 3,000 interlocking Bilateral Air Service Agreements

Before an airline can operate international services, the government of the respective countries must negotiate a treaty level agreement which forms a platform of international air transportation. These negotiated treaties are defined as the Bilateral Rights or Bilateral Air Service Agreements. These agreements universally comprise the following components:

- Traffic Rights or the Freedoms of the Air – the routes that airlines can serve and with what frequency.

- Capacity deployed – in terms of seat allocation or passengers carried.

- Designation, Ownership and Control – type of aircraft, ownership and operation control. The agreement might also include foreign ownership restrictions.

- Tariffs – might require submission of ticket prices to aeronautical authorities by airlines.

- Competition policy, safety and security component.

THE NATURE OF AGREEMENTS

International aviation is regulated by a complex web of over 3,000 interlocking Bilateral Air Service Agreements. When more than two countries come together as a group to negotiate such agreements, these are referred to as multi-lateral or pluri-lateral agreements. Nevertheless, the majority is traded bilaterally. As per the status in 2005-06, India had signed Bilateral Air Service Agreements with 101 countries broadly divided into seven regions, namely North America, South America, Africa, South East Asia, CIS countries, Gulf including West Asia as well as South Asia.

These agreements were majorly based on exercising up to the fifth freedom of the air, originating from the Chicago Convention, 1944, that designates a carrier the right to fly between two foreign countries, while the flight originates or ends in one’s own country, with a few exceptions like Singapore and Kathmandu that might extend beyond the fifth freedom. After this, some modifications had been made in 2009 in the memorandums of understanding (MoUs) with Malaysia, Singapore, Uzbekistan, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Jordan and Iceland. Next, the two most vital parameters that are considered while formulating these MoUs are the capacity deployment and the points of call. The capacity deployment is in terms of the number of seats per week, frequency of flight and the type of aircraft.

With the US, India shares an open sky policy that allows both the partners in the agreement to deploy unlimited capacity between their boundaries with no constraints on aircraft type. Rest of the leading bilateral agreements in terms of capacity deployment are Canada, China, Singapore, UK, France, Germany, Bahrain, Oman, UAE (excluding Dubai), Bangladesh and Sri Lanka ranging from 12,000 to 27,000 seats per week.

But the destinations that have gained commendable limelight of late are Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Singapore due to the increasing domination of the Middle Eastern and South Eastern carriers like Emirates, Etihad and Singapore Airlines. This had happened with the backdrop of the joint venture deals between Jet-Etihad, Tata-SIA (Singapore International Airlines) and Tata-AirAsia, after the Indian Government enhanced the foreign direct investment (FDI) limit on foreign carriers up to 49 per cent.

Last year, the entitlements between India and Abu Dhabi were increased to 50,000 per week and from the winter schedule 2014-15, the seat entitlements between India and Dubai would be 64,084 per week. But the strategic alliance of Jet Airways and Etihad, adding a further 42,000 seats per week for Jet Airways, have triggered their capacity growth to over 90,000 per week, following which increasing pressures have been witnessed on the home government from Sharjah, Qatar, Dubai, Singapore and Thailand. These negotiations were succeeded by the permission granted to the foreign carriers to operate Airbus A380 to the four major metro airports from May 2014, starting with SIA and followed by Emirates. Prior to this the international carriers mainly operated up to category 4E aircraft like Boeing B-747 and B-777.

TRAFFIC PATTERNS

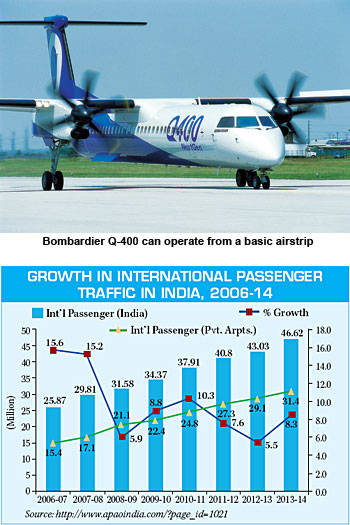

Before proceeding to the criteria of the points of call, it is necessary to have a comprehensive idea about the international traffic to and from India. From the graph below we can get a glimpse of the growth in international passenger traffic in India from 2006 to 2014 along with the year-on-year growth. Considering the entire range, traffic has grown by a remarkable 80.20 per cent. This growth was pan-India out of which in 2013-14, the five private airports at Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Cochin catered to 67.35 per cent of the total international traffic.

The second vital criterion is negotiating the points of call between countries. Here, the ground rules are set by the Freedoms of the Air that had been mentioned before. Points of call are nothing but the cities that an international carrier can serve in a foreign country. The illustration of the international traffic growth incline towards the five major private hub airports of India along with Kolkata and Chennai that cater to more than 70 per cent of India’s international air traffic.

Though the limelight is mostly restrained by the Middle Eastern carriers to have domination over the Indian international market, a commendable understated player who has been very aggressively seeking to expand their bilateral capacity from 14 to 56 flights weekly is the Turkish Airline enabling it to offer double daily services to Delhi and Mumbai and daily services to Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad and Kolkata. Apart from Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and Chennai the bilateral agreements of India identifies 18 such points of call namely Patna, Lucknow, Guwahati, Gaya, Varanasi, Bhubaneswar, Khajuraho, Aurangabad, Goa, Jaipur, Port Blair, Cochin, Thiruvananthapuram, Kozhikode, Amritsar, Visakhapatnam, Ahmedabad and Trichy.

In developed agreements where the traffic potential is huge, the points of call get evolved into three to four route schedules. Now the inter-dimensional conflict of interest arises when the traffic rights, i.e. the freedoms of the air tend to get exploited through various strategic shifts. When a joint venture like Jet-Etihad, Vistara or AirAsia-India is formed through the easing of FDI norms, there is always a threat of the foreign carriers getting the benefit over the domestic carriers. These strategic alliances allow the foreign carriers to exercise sixth, seventh, eighth and ninth freedoms of the air through their domestic counterparts and then taking over beyond the borders. For example, Jet Airways may carry passengers on intra-city routes to hubs like Delhi and Mumbai who are originally destined for say some European destination like Frankfurt.

Beyond the domestic hubs, Etihad might take over gaining strategically on the total segment, which otherwise would not have been allowed by the Indian Government. There is no mechanism to monitor the type of traffic whether point to point or carry forward, is being picked up by the consortium as these multidimensional itineraries are a complex web of code shared and transit traffic which is carefully encoded by the carriers. The only benefit to the Indian carriers is the much needed capital infusion and the inexpensive air turbine fuel (ATF) from the Middle Eastern and South Eastern hubs over feasible long-haul aircraft stage lengths.

But, on a macro level, the burden has to be borne by the domestic carriers who lose out on the potential international traffic that is compounding every year. As per CAPA (Centre of Asia Pacific Aviation, among the international market share to/from India held by airlines, Emirates claimed the highest, followed by Air India, Jet Airways, AI-Express, Qatar Airways, Air Arabia, Singapore Airlines, Thai Airways, Sri Lankan Airlines and Lufthansa respectively. Air India, the traditional market leader on international routes, was impacted by the chronic disruptions of its B-787s.

EMERGING BATTLEGROUNDS

An open skies agreement was signed between India and the United States in 2005 resulting in unlimited seat deployment between the two countries, which replaced the Indo-US agreement of 1956 that had placed various constraints over frequency, pricing, points of call and aircraft, with seamless code-sharing between Indian and US carriers. Although it was feared, the agreement has not yet led to a domination of US carriers on Indo-US routes.

On the contrary, the domination is depicted aggressively on the Middle Eastern and South Eastern routes by the Gulf carriers and Turkish Airlines. A new dimension has been highlighted through the network expansion of the global airline alliances – Star Alliance, Oneworld and Sky Team. Though membership of Air India of the Star Alliance would be a strategic advantage to the carrier’s turnaround plan, from another perspective it requires enough diligence to prevent the interest of the Indian carriers from being compromised.

Under the facade of short-haul international routes in the Middle Eastern and South Eastern skies, what needs to be kept in mind is the new battleground of the long-haul American and European segments. Approximately 30 per cent of Air India’s revenues come from the North American routes where the Gulf carriers have increased capacity over 30 per cent in 2014 and utilising the increased seat entitlements gained from the revised bilateral agreements and strategic alliances through FDI, as feeder routes to quench these additional capacity.

Recently the traffic growth in the long haul routes of North America, UK and Europe has marginally decreased in comparison to the total international market of India, which is in contrast to the eight to 12 per cent growth in the short-haul Middle Eastern routes. Nevertheless, the aggressive expansion endeavour of the Gulf carriers in the Western skies is an indication of the new emerging battleground.

It is high time the government proactively optimises and devises feasible Route Dispersal Guidelines through which it has identified 87 incentive destinations, because many of these destinations have barely a basic airstrip that is not suitable for the operation of an Airbus A320 or Boeing B-737 and thereby requires acquisition of additional Bombardier Q-400 or ATR airliners by the major existing low-cost carriers, burdening them with further cost. A comprehensive synchronisation of operating framework is the need of the hour within and beyond the boundaries.