Airline Safety - Turmoil in Iceland

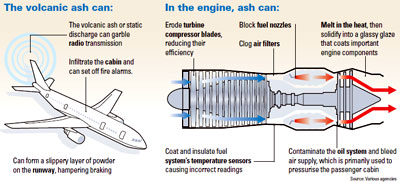

A cloud of uncertainty, far larger than any volcanic ash cloud, is hanging over the global aviation industry as airlines, airports and regulators seek to learn lessons from the airspace shutdown that followed the eruption of the Eyjafjallajokull volcano in Iceland in April.

It all started with an innocuous message from Eurocontrol’s Central Flow Management Unit (CFMU) on the evening of April 14 noting that a plume stretching to flight level 220 had started streaming from an Icelandic volcano, designated Eyjafjoll.

“Area control centres affected may request CFMU to apply appropriate air traffic flow-control measures, such as zero-rate regulations. In the meantime, aircraft operators are strongly recommended to closely monitor all relevant notice to airmen (NOTAMs),” the message said.

Within hours, the global airline industry was thrown into turmoil with the biggest single airspace closure since 9/11 hit the airways—yet another unscheduled cost in an already vulnerable industry.

As the plume height quickly increased to FL350, concentrated ash carried by northerly air streams presented an early threat to Shanwick oceanic airspace and eastbound North Atlantic tracks were shifted slightly to the south.

CFMU started organising teleconferences within four hours to enable air navigation providers and airlines to discuss the impact and receive updates from the London Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre with new forecasts produced every six hours.

Air traffic control centres in Scandinavia such as Bodo and Stockholm were the first to declare that they were closing airspace sectors and instructed airliners to cancel flight plans and refile to alternate airports.

Shanwick oceanic control moved westbound North Atlantic tracks further south on April 15. But the adjustment to transatlantic routes was rapidly becoming a minor issue compared with the situation affecting continental airspace.

Oslo, Stavanger, northern Stockholm and northern Copenhagen airspace sectors moved to “zero rate” operations, unavailable to instrument flight rules traffic as a result of contamination from the volcanic ash cloud. This restriction also applied to the UK, north of Birmingham including the whole of Scotland and extended to Ireland shortly afterwards.

CFMU broadened the teleconference capacity as demand for participation increased. Knock-on effects rapidly became apparent. Zurich airport became congested with delayed aircraft as airways were cut off and refused to accept diverted flights.

Spread of the ash to the European core area, within 48 hour of the initial warning, crippled air traffic across the continent and beyond. Asian and North American flights bound for Europen were warned via the CFMU to carry “sufficient fuel to divert” as Germany shut down, along with the Maastricht upper area centre, northern France and states as far east as Poland, Finland and Estonia.

As the domino-effect closure spread southwards, as far as northern Italy and Spain, national authorities in more than 20 countries declared airspace unavailable, several of them enforcing a total prohibition on commercial traffic, effectively closing some 300 airports.

Eurocontrol states, which normally deal with around 28,000 flights daily, recorded a fall of 79 per cent in this figure as the crisis peaked on April 17 and 18.

Gradually, the dispersal of the volcanic cloud and changes in the altitude of potentially harmful ash enabled airspace on the fringe to reopen and other control centres to start accepting over flight traffic, before Eurocontrol and national regulators agreed on April 19 to reduce the “no-fly” region substantially—to betterdefined areas of dense contamination — clearing the way for the eventual resumption of flights.